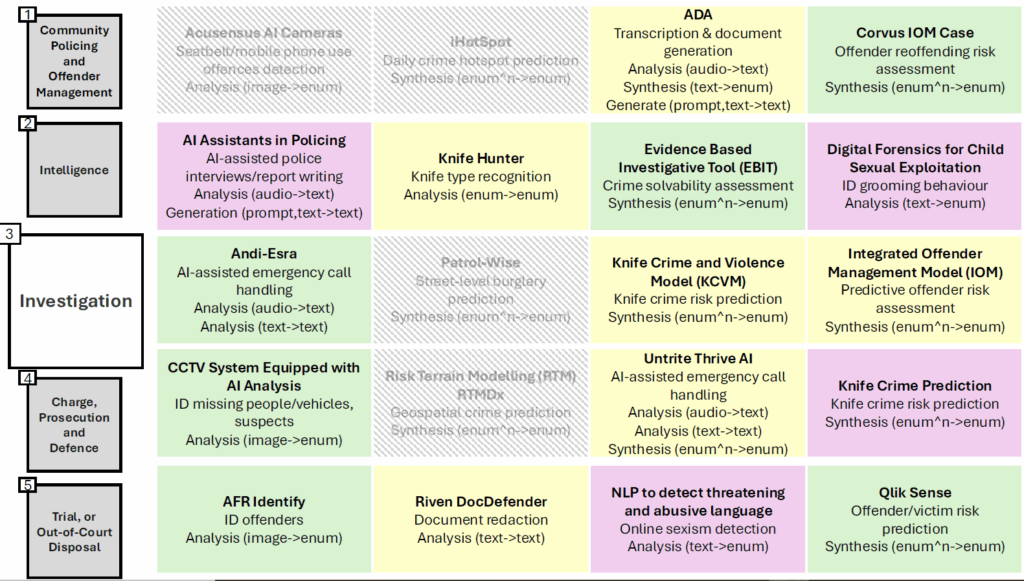

Figure 1: Excerpt from mapping exercise

In this post, Dr. Temitope Lawal and Katherine Jones of Northumbria University drew together some of the key themes and insights that emerged from a recent workshop co-delivered by PROBabLE Futures and the Alan Turing Institute, with a particular focus on criminal innovation, mapping technology in policing, and the need for regulatory reform.

It is now almost impossible to ignore the role artificial intelligence (AI) plays in shaping both the nature of crime and the ways society seeks to prevent and respond to it. In the UK and beyond, AI is already being used to facilitate fraudulent bank transfers through deepfake video impersonations, manage multiple victims in romance scams using multilingual chatbots, and even produce synthetic child sexual abuse imagery using fine-tuned generative models. These concrete examples – some involving tens of millions of pounds in financial losses or thousands of criminal images – formed the core subject of a workshop co-delivered by PROBabLE Futures and the Alan Turing Institute’s Centre for Emerging Technology and Security (CETaS) on 12 March 2025. The workshop brought together researchers, practitioners, and policy experts to examine how AI is reshaping both criminal activity and the institutions tasked with responding to it. Rather than centring on speculative threats or abstract ethics, discussions focused on the practical and rapidly evolving ways AI is already transforming criminal techniques, exacerbating harm, and challenging conventional justice processes.

Criminal innovation: AI at the service of deception

A recurring theme was the sheer pace and sophistication of criminal adaptation. Criminal groups are no longer simply reacting to AI but are actively driving innovation. A widely discussed case involved a Hong Kong-based financial fraud, in which a company employee was deceived into transferring $25 million after attending a video call with what appeared to be senior executives, only later revealed to be AI-generated deepfakes. In another domain, romance scammers are now using large language models (LLMs) to craft emotionally persuasive messages, test different phrasings, and manage simultaneous conversations across languages using AI-driven translation. Such developments are not one-off anomalies. They reflect broader shifts in the criminal ecosystem. Workshop participants noted a trend towards the automation and scaling of fraud, child exploitation, and online scams. As tools become more accessible (particularly through open-source releases or commercial leaks), techniques spread quickly across forums, with bad actors sharing not only content but also training data and model prompts.

The changing nature of online harm

Nowhere is the impact of AI more disturbing than in the area of child sexual abuse material (CSAM). Research presented during the workshop revealed an increasing number of AI CSAM images being shared on the dark web. In one study, a total of 3,512 CSAM images were scraped from a dark web forum, with 90% of these images being assessed as ‘realistic enough to be assessed under the same law as real CSAM’. The ability to generate custom, high-severity material, often based on real victims whose abuse images have been used to train new models, raises profound challenges for detection, takedown, and victim safeguarding. The workshop also discussed new coercive practices, such as AI-enabled “sextortion.” In such cases, perpetrators can create fake but convincing explicit images of children from innocent photos and use them to blackmail victims. Here, the realism of the AI-generated content renders the distinction between ‘real’ and ‘synthetic’ increasingly irrelevant from the victim’s perspective. The emotional and reputational harms are equally acute, regardless of whether the image was computer-generated.

Mapping AI in policing and justice

In response to these growing threats, the workshop featured a systematic and collaborative work being designed by the PROBabLE Futures team that maps the use of AI tools across the UK criminal justice system.

A structured taxonomy was introduced to classify tools by their functions – such as analysis, synthesis, and generation – and the types of data they process. The mapping exercise reflected where in the criminal justice process – what we term the 8 stages of criminal justice: community policing and offender management -> intelligence -> investigation -> charge, prosecution, and defence, -> trial, or out-of-court disposal -> sentencing, fine, or other penalty -> prison and parole -> release and probation – different types of AI tools are either being experimented, trialled, or deployed. The findings (see figure 1 for an excerpt) revealed a clustering of tools around the first three stages (offender management, intelligence gathering and investigation), with limited uptake at later stages such as prosecution or sentencing. Generative AI, despite its public visibility, was not yet widely used in these domains, but participants agreed that its use in trial preparation or evidence presentation is likely on the horizon. Another important insight was the need to understand how tools interact across stages. If an AI tool used in intelligence produces outputs that feed into an investigative decision, and eventually shape courtroom evidence, how are those links documented, challenged, or reviewed? This “chaining” of AI outputs through the justice pipeline presents significant governance challenges, particularly in ensuring accountability and fairness.

Data, lived experience, and participatory design

Several contributors stressed the importance of complementing technical solutions with grounded knowledge. In particular, the work of civil society organisations such as Stop the Traffik highlighted the value of combining structured data scraping with lived experience accounts to surface risk indicators of human trafficking. Adverts on adult services websites, when linked to repeated keywords, shared contact details, or certain geographic patterns, can reveal exploitation networks; but only when interpreted alongside the stories of those with direct experience. This approach underscored a broader point: AI is only as effective, and as ethical, as the data and assumptions it is built on. Building in qualitative insights, subject-matter expertise, and transparency mechanisms is critical not only for accuracy but also for public trust.

Regulation, responsibility, and the role of open models

From a regulatory perspective, the challenges are substantial. While UK law is relatively robust in criminalising realistic and synthetic CSAM, the legislation was not designed with generative AI in mind. Participants discussed how current legal and technical frameworks are often outpaced by the speed of model development and deployment, but also acknowledged governmental efforts in evolving new legislation, such as the recent Crime and Policing Bill, which introduces new provisions that criminalise use of AI models that have been optimised to create CSAM. Relatedly, one contentious area of discussion was the tension between open-source AI and closed commercial systems. Openly released models, like early versions of Stable Diffusion, were quickly repurposed for harmful uses, including abuse generation. Yet commercial tools, while often more controlled, also raise concerns about lack of transparency, oversight, and accountability. There was consensus that neither self-regulation nor banning open-source development would be sufficient. Instead, the focus must be on layered safeguards: filtering training data, restricting harmful prompts, and implementing robust output moderation. Academic institutions and startups, too, have a role to play in anticipating the downstream risks of the tools they develop.

Conclusion

The workshop concluded with a clear message that AI is already transforming the landscape of crime and justice. Responses must go beyond reactive fixes. They must be forward-looking, systemic, and grounded in both technical expertise and human insight. Building effective and ethical responses will require collaboration across sectors, clear accountability frameworks, and an openness to rethink how justice systems understand and respond to harm.

About PROBabLE Futures

PROBabLE Futures, one of Responsible AI UK’s keystone projects, is a four-year interdisciplinary research initiative focused on evaluating probabilistic AI systems across the criminal justice sector. The project, working alongside law enforcement, third sector and commercial partners, is developing a framework to understand the implications of uncertainty and to build confidence in future Probabilistic AI in law enforcement, with the interests of justice and responsibility at its heart.